Bioregional’s Nicholas Schoon confronts the thorny issue of the UK’s consumption-based footprint

The UK’s ‘real’ carbon footprint -emissions of climate-changing gases caused by our consumption of goods and services – are rising, according to government figures published this week.

Usually we think about UK carbon emissions in terms of tonnes of gas generated within our own island borders, chiefly from burning fossil fuels in cars, power stations, industrial plants, central heating boilers and so on.

These ‘territorial’ emissions have been falling for quarter century. They are the ones covered under the UK’s carbon cutting targets and its world-leading Climate Change Act. Happy days.

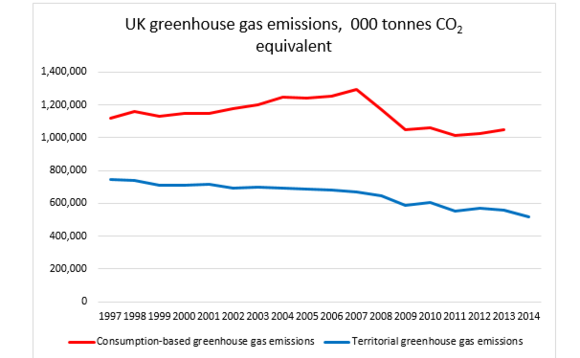

But the story of our other, ‘real’ footprint – the consumption-based one – is not so happy. Between 2011 and 2013 emissions of these greenhouse gases rose by 4 per cent. Here are the two footprints, territorial and consumption-based, travelling through time together.

Two things stand out. For most of the period, the two graph lines have been headed in opposite directions. And the consumption-based carbon footprint is much larger than the territorial one.

Just over half of the consumption-based carbon footprint consists of greenhouse gas emissions that happened outside the UK, in other countries. The gases were released into the atmosphere producing goods and services destined for consumption in Britain – from iPads made in China through cars assembled in Germany to call centre conversations with India.

To calculate this ‘real’ footprint is far from easy. It requires working through a mass of international trade data, trying to attach carbon emissions to the recorded flows of goods and services. That partly, but not fully, excuses the very long wait for the latest figures – only in August 2016 did the government published its UK carbon footprint for 2013. It’s actually a team at Leeds University which does the clever work involved.

Is it reasonable to focus on these emissions and their not-so-happy story rather than the sunny ‘territorial’ figures? It is. For decades, the UK has been gradually and perhaps unwittingly moving its economy away from high-emissions manufacturing into lower emissions services. So while we continue to consume plenty of manufactured goods, the emissions this consumption causes are increasingly offshored. We need to understand and acknowledge this; estimating our consumption-based footprint tries to bring some numbers to that process.

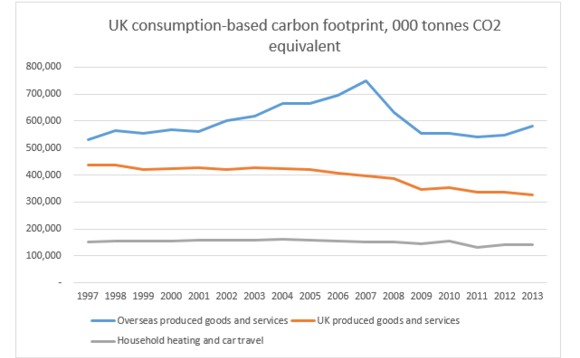

What is going on with this footprint? To see that, we have to divide it into three principle components: 1) emissions linked to those goods and services we consume which are imported from overseas, 2) emissions linked to our consumption of goods and services made in Britain and 3) those ‘household’ emissions most directly under our own control, from our car travel and heating our homes.

Household emissions have been flat or, more recently, falling. Emissions from UK-produced goods and services fell significantly over the 16-year period, as the UK made a start on decarbonising its electricity grid and the entire economy.

But what of the largest components of our consumption-based footprint, the emissions caused by the goods and services we import? They rose fast between 1997 and 2007, then fell for four years before starting to rise again. That fall was caused by the global financial crisis and recession (we imported less as our economy shrank) and by a period of high fossil fuel prices which tend to make our imports less carbon intensive.

But what about the more recent, resumed increase in these ‘imported’ emissions? We’ll have to wait a couple of years to see if this is a trend. But the growth from 2001-2013 suggests the UK’s trading partners, taken as a whole, are not yet decarbonising their economies…or doing it very slowly.

Which brings us to Brexit, and the Brexiteers’s stated wish for the UK to have a bigger share of its trade with the world’s fastest growing economies rather than the sclerotic, slow-growing European Union. The Leeds University analysis assigns imported emissions to individual countries which Britain trades with. Here is how they divide up between the European Union, China and rest of the world.

What jumps out of this graph? First, the astonishing importance of Chinese imports in Britain’s real carbon footprint. This single country was responsible for 11 per cent of the UK’s total consumption based-carbon footprint in 2013.

Second, import-linked emissions fell for all three blocs (China, the EU and the rest of the world) for a few years as imports shrank in the wake of the financial crisis and recession.

Third, import-linked emissions from China and the rest of the world look as if they are back on a rising trend in the aftermath of the recession. Import-linked emissions from the EU appear to be on a decade-long falling trend, although they ticked upwards between 2012 and 2013.

It may be off-message to say we should trade enthusiastically with the decarbonising European Union if we want to keep control of the UK’s real carbon footprint. But we should. If we are serious about tackling climate change and remaining a world leader in that field, then we need to pay attention to the emissions embedded in our imports, and bring these into our trade negotiations.

The optimism of last December’s Paris Climate Summit now seems a long way in the past. Climate change is gathering pace, with temperature records being broken month after month and Arctic sea ice cover fast disappearing.

A few days after the Brexit vote, a paper published in the leading science journal Nature looked at the prospects for limiting the rise in average global temperatures to less than 2 degrees Centigrade, the core goal of the Paris agreement. Hardly anyone in Britain noticed; we had other things on our mind.

That paper, written by an international team of scientists, found the existing carbon-cutting pledges made by countries in the run up to Paris implied an average warming above pre-industrial levels of 2.6 to 3.1 degrees C.

As for world leaders’ agreement there to “pursue efforts” to limit warming to below 1.5 degrees C, they are almost certainly too late. The scientists conclude: “The window already seems to have vanished.”

Now, more than ever, the planet needs leadership on climate change. Paying attention to consumption-based carbon footprints is an important part of that.

Nicholas Schoon is policy and communications manager at Bioregional

Further reading

Source: Climate Change

Original article: Our real carbon footprint is still rising